Why Tyler Rogers Works: Inside MLB’s Most Extreme Arm Angle

If you’ve ever watched Tyler Rogers pitch and thought, this can’t possibly work in the modern era, congratulations you’ve just described exactly why it does.

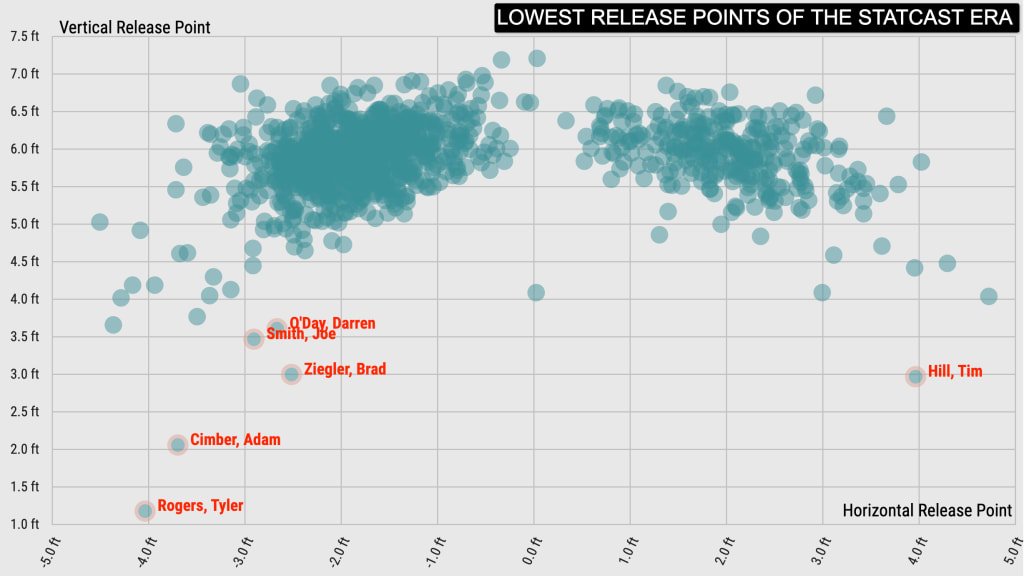

In a sport increasingly obsessed with 97 mph, vertical ride, and optimized spin efficiency, Rogers shows up like a glitch in the system. He releases the ball from a place your eyes aren’t trained to look, at an angle your brain doesn’t expect, with movement that feels less like physics and more like sleight of hand. Statcast tracks his release point at roughly 1.3 feet off the ground, an absurdly low number by Major League standards, and one that immediately separates him from almost every pitcher hitters face over the course of a season.

That extreme release isn’t a novelty. It’s a plan.

Tyler Rogers didn’t arrive in professional baseball with pedigree or hype. He was a 10th-round pick, the type of selection teams make hoping for organizational depth, not leverage innings. He pitched at Austin Peay State, not exactly a national powerhouse, and climbed the ladder the slow way by proving, level after level, that the delivery wasn’t a trick and the results weren’t an accident.

He’s also half of one of baseball’s most unusual family dynamics: the twin brother of Taylor Rogers, a left-handed reliever, while Tyler throws right-handed. Mirror-image twins in a sport that rarely produces symmetry, let alone dual bullpen relevance. That detail matters. It hints at the way Tyler is wired as routine-driven, comfortable being different, and deeply committed to repetition. In a profession built on muscle memory, which isn’t trivia, it’s a competitive advantage.

Mechanically, Rogers operates in a space that hitters simply don’t rehearse. Most professional hitters train their eyes to pick up the baseball from a relatively narrow band of release heights and arm slots. Rogers releases the ball from below knee level, with an extreme sidearm (submarine) delivery. The pitch enters the hitter’s visual field later and from farther outside their expected line of sight. That delay compresses decision time. Even when hitters “know” what’s coming, their brains don’t get enough clean visual information early enough to react comfortably.

Hitters don’t just react to velocity; they react to time-to-recognition. Rogers shortens that window so that the pitch looks slow on the scoreboard, but it feels rushed in the box. By the time the hitter fully identifies spin and trajectory, the swing is already half-decided.

Statcast data reinforces this where Rogers doesn’t live on strikeouts; he lives on contact manipulation. His pitches arrive on a flatter, lower plane that intersects modern swing paths late, forcing hitters into weak topspin contact, rolled-over ground balls, and off-balance takes at the bottom of the zone. Baseball Savant’s visual reports show tightly clustered release points and consistent movement profiles. Weird, yes, but critically, repeatable.

That repeatability is why the league hasn’t “figured him out” in the way skeptics always predicted because hitters can adjust to odd if odd is wild but they struggle when odd is precise.

If you asked a hitting coach to design the ideal plan against Tyler Rogers, it would sound straightforward on paper: stay on top of the ball, don’t chase below the zone, let it travel, use right-center, shrink the vertical strike zone. In theory, a disciplined hitter should neutralize an 83-mph pitcher by refusing to expand.

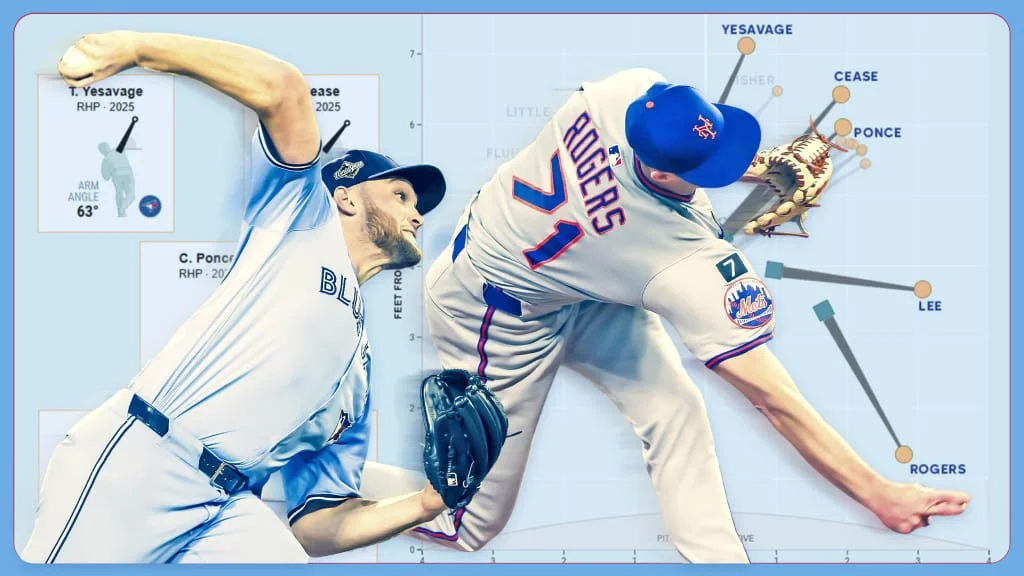

That graph immediately tells a story: Rogers’ arm angle is almost 5x lower than a conventional starter and a full 6 feet lower than Yesavage’s over-the-top slot.

Think about what that means for a hitter:

With a 6’5″-ish slot like Gausman’s, the ball drops into the zone from above, seeming to fall into space.

With Yesavage’s 7+ ft slot, the ball practically rains down on the zone with steep perceived tilt.

With Rogers, the ball starts below eye level and rises into contact. It’s unfamiliar and unfamiliar equals hesitation.

This is why hitters describe Rogers’ delivery as an optical illusion where the ball seems to “pop” up and at MLB fastball and slider velocities, that’s all the anxiety you need to force weak contact.

Advanced Analytics: Release Point, Spin, and Deception

Metrics like CSW (called strikes + whiffs) and extension help quantify why someone like Rogers can survive, and thrive, despite conventional wisdom suggesting his low velo (~82–85 mph) shouldn’t be major-league effective.

Rogers’ sinker and slider generate movement profiles that are abnormal by both spin and trajectory is the kind that confounds models built for straight-over-the-shoulder deliveries. Broader analytics show that Rogers’ fastball has a spin axis near levels other pitchers might see only on breaking balls, and his curve/sweeper sinkers drop nearly 8 inches below expected levels for similar pitch types.

This combination of extreme release point + deception + movement is why hitters struggle even when the radar doesn’t flash triple-digit velo.

His unique delivery also shows up in induced movement patterns which makes batters swing under or late on pitches that look straight until the very last split second, where the ball darts or dances unpredictably.

So…in practice, the hitting coach’s plan collapses under timing pressure. Rogers’ release point forces hitters to start earlier to avoid being late. That early commitment leaves them vulnerable to the subtle horizontal movement that arrives just as the bat enters the zone. The result is familiar: hesitant swings, defensive contact, or frozen takes on pitches that nick the bottom edge. It’s not ignorance, it’s miscalibration.

That’s why his success doesn’t show up in highlight reels. It shows up in pitch counts that reset innings, double plays that erase threats, and leverage moments that quietly swing games.

Rogers exists at the far edge of a rare fraternity. Baseball has seen effective low-slot relievers before (Darren O’Day, Brad Ziegler, Pat Neshek) but even among that group, Rogers is an outlier. Statcast’s arm-angle tracking places him among the most extreme pitchers in the sport, not intermittently, but every single outing. He doesn’t drift into the slot. He lives there.

That consistency is what separates him. Many sidearm pitchers flash success before hitters adjust to variability but Rogers denies that adjustment. There is no “normal” look to reset against. Each at-bat feels unfamiliar, even when the scouting report is clear.

For front offices, this has real roster value because pitchers like Rogers don’t just collect outs; they invalidate assumptions, they force opposing managers to burn bench bats, disrupt platoon plans, and they abandon carefully constructed game scripts. In postseason baseball, where preparation is meticulous and margins are razor thin, that disruption is priceless.

This is why teams like Toronto increasingly emphasize arm-angle diversity as a deliberate organizational strategy. It’s not about replacing power arms. It’s about sequencing discomfort where, after seeing 96 from over the top, 83 from the dirt feels like a trap door.

Off the field, Rogers fits the profile teammates trust which is great because bullpens are emotional ecosystems. They value reliability, humility, and adaptability. Rogers’ career path of being a late pick, with a slow climb, but demonstrating constant proof tends to produce professionals who accept irregular usage and pressure without theatrics. He’s the pitcher managers deploy when they want the inning to feel chaotic for the opponent and calm for their own dugout.

There’s also a quiet longevity baked into this archetype. Velocity fades and deception ages better. Arm slots don’t erode the way fastballs do. As long as Rogers can repeat the delivery and command the zone, his effectiveness is insulated from many of the trends that shorten pitching careers.

That’s the part casual observers miss. Tyler Rogers isn’t surviving in spite of modern baseball, but he’s actually thriving because of it. In a league that trains hitters to solve one problem, he keeps changing the question.

He’s not a gimmick. He’s not a trick. He’s a design choice rooted in geometry, perception, and psychological disruption.

And in October, when every lineup is deep and every hitter has a plan, the pitcher who forces them to throw the plan away is worth far more than his radar-gun reading suggests.

Sources

https://baseballsavant.mlb.com

https://baseballsavant.mlb.com/leaderboard/arm-angle

https://www.mlb.com/news/blue-jays-pitching-staff-arm-angle-diversity

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tyler_Rogers_(baseball)

https://www.mlb.com/glossary/statcast/release-point

https://blogs.fangraphs.com/how-arm-angle-changes-hitter-perception

https://www.mlb.com/news/why-submarine-pitchers-are-so-rare